I like Keriya

It’s an authentic place, one still shaped by the people and the lives around.

It’s certainly not been developed, like the other places in Southern Xinjiang ivevisited – no massive plans, no huge changes in infrastructure. Keriya is still a place of small lives.

The sky was a radiant blue, a blue unlike the smog in Kashgar or dust of Hotan. As we wandered we took dozens of pictures – and attracted the attention of some kids. So we showed them some of our pictures and zombie videos, and then shot a few more short clips with them (with J actingas a zombie monster emerging from a dark doorway, and the kids laughing in mock terror) before wandering on. Pictures – and videos – are great breakers of cultural boundaries.

Until mosque let out the town was nearly silent. Ali told me that 100% of men go to mosque, and I didn’t believe him, for this isn’t the case in Urumqi or Kashgar. But in Keriya the entire town is empty for that one hour, barely a man to be seen on the streets, ‘cept a few policemen, restaurant owners, and entrepreneurs selling sliced fruit and snacks to the mass of hungry men emitted at four pm. The entire place goes from bustling to deserted in the quarter-hour before three.

We walked by the brother’s naan shop and talked to the lively worker who makes naans nonstop during the day. He lived in Beijing – in Shangdi for five years – and yet he too has returned to Keriya, to a small and steady job in a town that speaks his tongue (for there are near no Han Chinese in Keriya – they’re kind of like elephants: out of place and easy to spot).

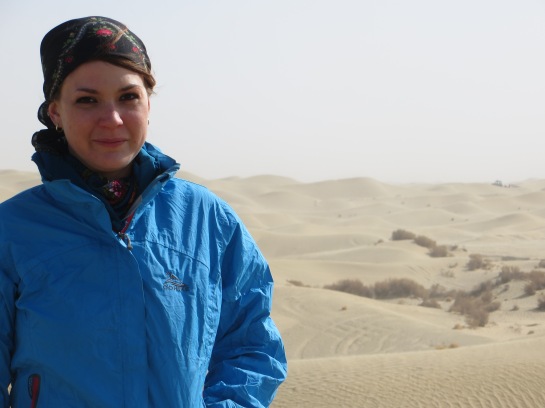

When mosque let out there was first a trickle and then a flood, a veritable flood of men in black coats and tall hats. For half an hour women were scarce on the street, their numbers overwhelmed by the flow of men from the mosque back into their everyday lives. I felt baren, almost naked, for not wearing a headscarf. An object of attention – not critical or aggressive, just slightly startled, unsure attention. as in, HELLO! I’M OUT OF PLACE HERE! Almost all women here wear headscarves of some type, even younger children. In Aksu I saw one or two women with all but their eyes covered; in Kashgar, perhaps five percent (but some older women also completely cover their faces with loose brown shawls); and here, 99%of women wear headscarves, and in certain areas of town, 15-20% of them are completely covered, with but their eyes showing (though no one wears those brown shawl things). Wearing a headscarf has ceased to be a personal religious decision: it’s a community ultimatum, and there’s enormous unspoken pressure to conform.

As we made our way toward the mosque to find Ali, J was approached by a boy who wanted to speak English with him. This guy, it turns out, works as an interpreter in Urumqi and is home for the holiday. He seemed genial enough, and the two were planning on heading back around the same time, so they exchanged numbers. Which drew a huge crowd – five, then ten, then thirty men encircling them, just looking. The more men crowded round them the more came over to look and the larger the circle grew. This is a China phenomenon: whenever there are people crowding around something, more people have to go over and look. It’s also true that, until the barrier is broken (by a local interacting with us), people generally won’t intrude, will stare but won’t approach (except for the occasional “hello!”).

Keriya is noticeably more conservative than Kashgar – it’s like I’ve been traveling along an exponential graph, from Urumqi (comparatively liberal and free) to Aksu (moderate) to Kashgar (conservative but modern) to Hotan (conservative, not very modern) to Keriya (as conservative as rural Texas). I’m curious to know what happens further down the loop, to the towns no one I know has seen before, no one I know comes from: Niya, Qiemo, Ruoqian. But perhaps that will happen another time, in the summer when I travel to Kashgar once again.

Another interesting point: everyone in Kashgar thinks of themselves as more cultured (and, for northern Xinjiang, people in Yili/Ili/Gulgha take some pride in their hometown too). Hotan is seen as a backwater bayou: more crass, less historically significant, less refined (in the same way Savy New Yorkers might view uneducated Bostonians with their impenetrable accents, or the way the rest of the states views Alabama or West Virginia). But – I still like it, for the town is penetrated with an air of authenticity, like a wild west town that hasn’t been made into a film location.

A short anecdote: when I met them in Hotan, J told me that every meal he’d eaten had some form of mutton in it. Nothing is without meat (except breakfast, which is generally bread, jam and maybe yogurt). Several weeks back he, C, S and Adil went to a Uighur restaurant together for lunch. C is a vegetarian, and so she tried to order noodles (laghman) with vegetarian topping. Adil went to talk to the cook and a few minutes later he came back. “He can’t do it”. “What?” “He says he can’t make laughman without meat” (as in, it’s literally impossible for the man to not put meat into the vegetable and sauce topping for the noodles). And, indeed, our meals yesterday were: naan and fruit jam for breakfast, pilaf with yogurt for lunch, and noodles and kebabs for dinner, all chosen for us by our friends and local dietary decision-makers.